|

Life During the Bewitched Years

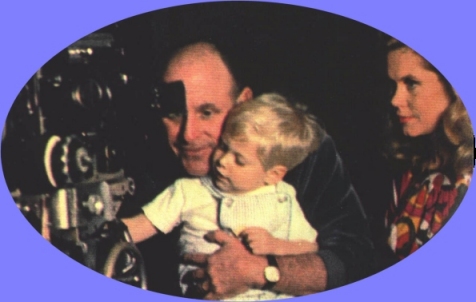

Director Bill Asher, Billy, and Elizabeth Montgomery on the Set of Bewitched Submitted by Jan W as originally appeared in the May 13-19, 1967 edition of TV Guide magazine in the article entitled "Rough, Tough, and Delightful: The Ashers Agree on What they Want, Including Who's the Boss" by Arnold Hano. Liz Montgomery stood before the camera on the Bewitched set in Hollywood the other morning when the shield fell from the camera light. Several hundred watts hit her smack between the eyes, temporarily blinding her. Liz staggered back, kept most of her cool and blinked a few times, and within 45 seconds was back in front of the cameras. Not all of her cool. She asked, "Where are we?" meaning where were they in the script. From behind the camera Bill Asher, director of Bewitched, who is also Liz Montgomery's husband, said briskly, "Stage 4. Bewitched. Shall we continue?" And they did. These are the Ashers, Liz and Bill. Technically, Bewitched – deep into its third successful season – is produced by Screen Gems, Inc. Technically, its producer (television's usual synonym for "boss") is Harry Ackerman. None of it matters. The Ashers run Bewitched. "They are liked the crowned heads of Europe," a spokesman says. "They are the mama and the papa of the set." It is, insists the spokesman, a benevolent monarchy, a happy family; and mainly he is right. Still, there are moments. Each Bewitched episode is shot in three days, and, let's face it, you can't shoot a clever station break in three days, much less a half-hour situation comedy. So when a script is more unpolished than usual–says Dick York, who plays the husband on Bewitched–"there is friction. We have too much to do too fast." Tempers flare. There are other exceptions to this benevolence. A Screen Gems executive tells of the time a guest star performed in a matter that did not quite meet with Liz's approval. "On the way home that night, she and Bill had a conference, and the guest star has not been on the show since. Nor will he be." Bill Asher is tough. "If you make a mistake," says Harry Flynn, the show's publicist, "he can give you a rough time. He's especially hard on phonies." Liz Asher is tough. "If an interviewer is not her cup of tea," says Flynn, "she can't sit down and be pleasant. She loathes pretensions." Nevertheless the Ashers are refreshing. They loath phonies, are direct and terribly honest. If they remind you less of the crowned heads of Europe, they remind you more of the Kennedys. Like the Kennedys, they are brisk, businesslike, tireless, hard-nosed, competent, personable, pragmatic, and intelligent. (Like the Kennedys, they even play touch football.) They are also in tune. When Liz acts Samantha, she keeps her eyes directly on her husband as he feeds cues to her. He beams, she beams; he nods, she nods; he smiles, she smiles. Asher judges actresses on a scale of 0 to 1000, and fits Liz into the 900 to 1000 bracket. "As an actress," he says, "there is nothing she can't do." Liz says, "Bill is the best director I've ever worked with." What they are, of course, are two people in love, which in Hollywood is a blast of fresh air. More surprising, after nearly four years of marriage, and a siege of togetherness unequaled since the last Siamese twins, they seem to like each other. They are living proof that opposites attract, she is the rich Beverly Hills girl and he the not-quite-poor boy from the streets of Manhattan. She is tall, slender, blonde and beautiful, looking still, at 34, the cool-eyed girl who danced till dawn at all the New York balls in 1951. He is short, squat, thick-necked and balding, like your friendly neighborhood wrestler. She went to swank finishing schools, danced with Andover boys and Harvard men, summered in England with her father, Robert Montgomery, and began her career at the Academy of Dramatic Art. Her father got her her first acting job–a starring role in his TV show. Asher never finished high school. He began his career as a $12-a-week mail boy for Universal when he was 13 years old; his father had just died, and he was on his own. The two careers converged when Liz appeared on a TV show that Asher directed in 1961. The relationship changed from a working one a few months later on the set of the film "Johnny Cool." Asher was the director; Liz the leading lady. "We loathed each other on first sight," Liz says. Bill agrees, but adds: "A few days later–wow!" They divorced their mates and married in October of 1963–her third marriage, his second–and began their total togetherness a month later with the making of the Bewitched pilot. These days they rise at 5:30 A.M. and drive to the studio. They work together until 7:15 P.M. and arrive home for their childrens' hour, at which time their sons William and Robert, are hefted, cuddled and put down. Then come the cocktails (while Liz studies her lines and Bill plans the shooting schedule), supper, and to bed. On weekends they play golf, tennis or both, together; they drive down to Palm Springs to party it up, and when they do, they are the last to leave, Liz deciding just before dawn that it's time to play the piano. "She does not really play the piano," a friend says. "She attacks it." Early the next morning they romp through a game of touch football on the lawn, to waken their muscles for the umpteen sets of tennis. "We work hard during shooting days," says Bill Asher, "to have more free time in evenings and on weekends. Our private life comes first." Liz agrees (for a reasonably head-strong girl, she defers to her husband in nearly all matters). This deference to her husband marks the new Liz Montgomery, one-time social butterfly. It is an old-fashioned deference, a return to the double standard. "If I am asked to make a publicity trip and Bill can't go along, I don't go. It's all right for the man to go off by himself. The man is the head of the family." Bill Asher is head of this family (nobody will ever call him "Mr. Montgomery.") He too subscribes to the double standard. Explaining the appeal of Bewitched, Asher sounds like a man tooting his own horn, the low-caste who has taken the rich-but-unhappy princess away from all that. "The show," he says, "portrays a mixed marriage that overcomes by love the enormous obstacles in its path. Samantha, in her new role as housewife, represents the true values of life. Material gain means nothing to her. She can have anything she wants through witchcraft, yet she'd rather scrub the kitchen floor on her hands and knees for the man she loves. It is the emotional satisfaction she craves." When asked whether he is defining his own philosophy of life and marriage, Asher says, "Completely." Material gains may mean nothing, but nobody is throwing them away. The Ashers have four cars – a Mercedes 220 SE coupe (his), a Jaguar XK-E (hers), a Chevrolet Corvette (his), and a Chevy station wagon (theirs). The latter two are company courtesy cars; General Motors is a Bewitched sponsor. The Asher's Benedict Canyon house is a huge affair right across from Harold Lloyd's fabled estate. They also own land in Northern California. Most important, they own 20 percent of the profits of Bewitched. It is reckoned that 20 percent of any show going beyond the third season (as Bewitched will) is worth $2 million. Still, Asher is right. The new Elizabeth Montgomery is the girl who craved, and has apparently found, emotional satisfaction. When Liz was in the third grade, she wrote a little poem:

But the days of being a butterfly turned out not so sunny after all. She danced with those Andover boys and Harvard men, and when she was 20, she married one of them (Frederic Gallatin Cammann, Harvard '51), but it lasted just one year. In 1955 she married actor Gig Young, but a friend of the couple at the time said, "Gig was the perfect actor-type. He had to be Hell to live with. He seems mainly concerned with his own appearance." Liz and Young once rented a furnished New York apartment. Here, Liz fell in love with a dishtowel – a white one with blue butterflies on it. She swiped it. This was no doubt a climax in the life of Liz Montgomery. When she swiped something, it turned out to be an item totally domestic, albeit festooned with butterflies. She and Young broke up in 1961 (the year she met Bill Asher), and the butterfly was dish-washed up. Liz has written a children's book (not published so far), and also dabbles in water colors and in quite-effective pen-and-ink sketches. Her art has a fetching quality. "I'd love to do water colors with Andrew Wyneth," she says, but adds firmly, "I know I never can." A friend therorizes, "Liz is not sure of herself artistically. She is not willing to put herself on the line until she is damn sure she is the best artist in the whole world." The friend likens this to Bewitched. "The show is fun, but no challenge. Lis is too happy being Samantha to try anything truly difficult." Or maybe Liz is simply too happy these days–being Elizabeth Montgomery Asher–to try anything else. When you ask her today about that verse, and which animal she know identifies with–the catepillar or the butterfly–the star replies indignantly, "Goodness, surely not the butterfly!" |