by Joseph N. Bell

Pageant

April 1965

|

Submitted by: Windjammer

These two television executives, Bill Dozier and Harry Ackerman, were having lunch in the fall of 1963. Their conversation went something like this:

And so, television being what it is, a witch series was born. And audiences being what they are, Bewitched has become the smash hit of the 1964-'65 television season. Along with fame, however, have come a few problems, not the least of which is how to continue cranking out episodes of Bewitched and still satisfy the burgeoning demand for personal contact by the press and public with the head witch - a lanky, piquant girl with a tip-tilted nose and a famous actor-father - Elizabeth Montgomery, daughter of Robert Montgomery.

Montgomery in the 1950s When Miss Montgomery crawled into bed last October 13th after a rugged day at the studio, she was about as well-known as any of several dozen other 30-year-old actresses who have done second leads on Broadway, several pale movies, and some reasonably demanding parts in television dramas - some of them quite good. When she reported for work the following morning, Elizabeth Montgomery found that fan writers were lining up to interview her and that her name had become a byword in the never-never land of network television.

Montgomery was a Starlet before Bewitched Why? Because readings had been taken from a scattering of homes across the United States by a rating service called Nielsen, and the gods had rendered their verdict: Bewitched, newcomer and rank outsider, had been proclaimed the second most looked-at TV show in America. Overnight Miss Montgomery was a celebrity and all the people responsible for Bewitched were geniuses. That's the way it is these days in television. What it all adds up to at the moment for Liz Montgomery is work. ("I've worked hard before," she says, "but never this long this hard.")

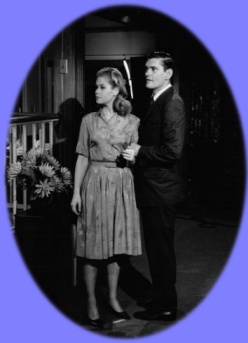

Montgomery and York on the Set of Bewitched After that luncheon conversation during which the idea of Bewitched was conceived by Dozier and Ackerman, George Axelrod, the noted playwright, was approached to do a pilot script for the series. "He loved the idea," says Ackerman, "but he was too involved in other projects to tackle it." So Sol Saks was hired to do the pilot, in which he had to explain how a New York advertising executive happened to have married a witch. Everyone involved in the project was excited about it, and while the pilot was still being written, Ackerman was looking for someone to play the witch. His eye hit first on Tammy Grimes, who was in temporary residence at Malibu Beach while she made a movie. Miss Grimes liked the idea of permanent employment and agreed to play the witch; then she was offered a lead in the Noel Coward musical High Spirits and begged off. Ackerman released her reluctantly. At this fortuitous juncture Elizabeth Montgomery and her third husband, writer-producer-director Bill Asher, appeared on the scene. Their mission at Screen Gems, which produces Bewitched, was to sell a TV series idea starring Miss Montgomery and directed by Asher. ("We'd rather not say what it was, since we still may do it someday.") The executives at Screen Gems didn't think much of their idea, but as he talked with the Ashers, Harry Ackerman mentally reconstructed his witch to fit Elizabeth Montgomery. She read the script, liked it, and made the pilot, with Asher directing. (It was then called The Witch of Westport.)

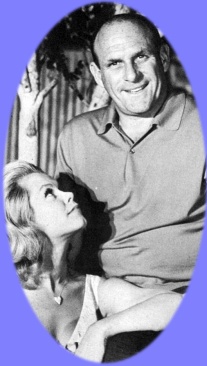

Montgomery and Asher During the First Season of Bewitched "This was one of those rare projects," recalls Ackerman, "where everything fell quickly into place and felt right to us. This idea came full-grown. Losing Tammy Grimes, we ended up with a different kind of witch, but one, I think, with whom housewives can find more empathy." The moment of truth for a TV pilot film comes when it is offered for sale. Bewitched was in almost immediate demand. Screen Gems prefers to sell to sponsors rather than networks ("If you sell to a network and they cool on a show, you have no place else to go."), and the first potential sponsors to look at the show bought it. By midsummer Bewitched was set for its present 9 p.m. Thursday ABC-TV slot. But Miss Montgomery, about to become a star, was also about to become a mother. The series couldn't start shooting until Liz was her old svelte self again.

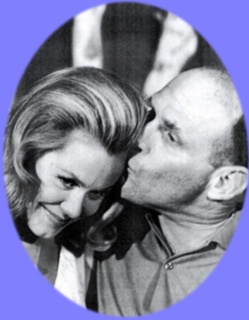

Liz Was In Love On and Off the Set of Bewitched Mrs. Asher gave birth to a son about five weeks before Bewitched went on the air. At that time there was only one show completed - the pilot. Normally, TV serials work from six to eight weeks ahead. Bill Dozier had meanwhile departed Screen Gems, leaving the show without a producer on the eve of its unveiling. Producer Danny Arnold appeared with a show called The Wackiest Ship in the Army that he wanted Screen Gems to take on. The studio liked the idea, but not for that season, so executive producer Ackerman hired Arnold for Bewitched. And three weeks before the show went on the air, the new producer, the recently unpregnant star, and the newly assembled cast and crew got together with urgent instructions to turn out a product as quickly as possible. They've been working at a mad pace ever since - a circumstance complicated by the smashing success of the show and the resultant demands from outsiders on the time of the already harassed people trying to get a few weeks ahead of the game. Not all of the people involved in Bewitched see it in the same perspective. Says Harry Ackerman, its affable, mild-mannered executive producer: "This show is a simple, honest extension of an elemental comedy idea that had gone about as far as it could go. We hit on a simple thing that sang and led us to marvelous story ideas: a witch trying to kick her witchdom. We didn't load it with too many frenetic characters, and we traded on simplicity. Sure, I enjoy carrying a message if it can be done within the terms of entertainment and the structure of the show. But there's great satisfaction in doing entertainment shows well and with quality."

Montgomery and York Were Magic Together on Bewitched Danny Arnold sees more profound implications than just entertainment in Bewitched. "With this show," he says, "I saw a great opportunity to accomplish something. Fantasy can always be a jumping-off place for more sophisticated work. We can make it identifiable with people and relate to problems that are everyday. What we do in this series doesn't happen to witches; it happens to people. But the messages are funnier when they happen to a witch - and therefore less offensive." What sort of messages? "Well, take the Halloween show. It pointed the finger at bigotry. Samantha's husband was prejudiced about witches - who are definitely a minority group. He thought they were all ugly old crones, and his wife had to break down this prejudice. It is a direct parallel to some of our social problems of today. But through fantasy, we can get a more vivid portrayal. Humor can then come out of touchy subjects." Did Miss Montgomery catch this assault on bigotry when she was making the Halloween show? In her cluttered trailer dressing room she wrinkled her nose thoughtfully and pondered the question. "I don't think it's that cerebral," she admitted. Then she added hastily: "But sometimes, whether you realize it or not, you're making a point. I don't think we have to justify a piece of work, though, on any other basis than entertainment. If the warmth comes through, that's what's important." Miss Montgomery resembles her father in a way that is difficult to pinpoint - perhaps most markedly in her generous mouth. She is rather tall, has attractive legs, a fair complexion, shoulder-length hair, corn-flower-blue eyes, and a slightly tilted nose. She is serious about her television work. (Editor's note: Her eyes were green.)

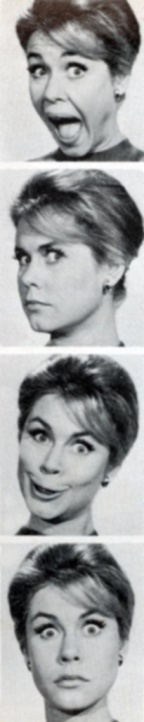

Actually,

Montgomery Shares Features "This is a real challenge to an actress," she says, "a challenge not to fall into the trap of letting the character play me instead of me playing the character. I try to approach each script as if it were an entirely new show. "Comedy is much, much more difficult to do than drama. Look at it this way: If you tell ten people in a room a sad story - about a child who was hurt, let's say - all of them will react with similar emotions. But if you tell these same people a joke, you may get ten different reactions. Most people will agree emotionally on a tragic situation, but not on comedy. Comedy depends almost entirely on how well you tell it. That's why this show is a constant challenge." As we talked, a press agent appeared in the dressing room to seek Miss Montgomery's decision on three requests for personal appearances. One came from the St. Paul Winter Carnival, another from the Charlotte (North Carolina) Flower Festival. A third requested her presence at the dedication of a new antenna for a Chicago TV station. Was Miss Montgomery interested? She wasn't. "How could I find time to do these things?" she sighed. "We never get a chance to rest. We finish a show on Friday morning and start reading the script for the next one on Friday afternoon. When my husband and I first came out here, we had a house in Malibu, but the commuting was brutal. Now we've rented a place in Beverly Hills, and we have a full-time, living-in nurse for our son. But it's a rugged life. I'm up at five-thirty in the morning and home at eight o'clock at night five days a week, and I have to read scripts over the weekend." Does Robert Montgomery approve of Bewitched? "Sure," his daughter answered. "He loves it. At least that's what he tells me on the phone. I haven't seen him since I started doing the show, but I talk with him often by telephone. Of course, he didn't want me to be an actress at all. He used to tell me all the pitfalls of the acting profession. But when he found out I was determined to do it anyway, he asked if I'd like to make my first professional appearance with him on his television show - almost fourteen years ago. Naturally, I was thrilled. We did them live in those days, and I don't think it really dawned on him that it was me until the night the show was televised. I played his daughter, and the first time we appeared in a scene together, he just stared at me for a few seconds. I was afraid he was going to say, 'My God, it's really Liz!"' When I asked if she considered a rather lightweight television serial to be something beneath her abilities as a serious actress, she seemed amazed at the suggestion. "I had turned down offers for television series before," she said, "but only because I didn't feel they were right for me - certainly not because I felt a series on TV was beneath me as an actress. I don't understand professionals who feel this way. All you have to do is look at the sound stage next door to see one of the greatest - Shirley Booth - working in a television series. She doesn't feel it's beneath her. Neither does Aggie Moorehead, who works on about half our shows."

Liz Shows Her Acting Range with this Sample of her Many Expressions Even on Christmas and New Year's Eve the cameras were whirring late into the evening on the Bewitched set. Today the hard work and frantic pace are softened in the sunlight of sudden success. But in television, success is always subject to the caprices of the rating systems. The same mystical figures that made Bewitched a smashing hit can reduce it to ignominy almost overnight. Producer Arnold has worked out a philosophy about ratings. He says: "There are two different approaches to ratings: the emotional and the intellectual. When you're in the top ten, you take the emotional approach - you know, a feeling of warm gratitude that the people show such fine taste in the programs they prefer. But if you're one hundred and fiftieth, you take the intellectual approach to ratings - that it is morally and intellectually dishonest to pass judgment on a piece of creative work on the basis of a tiny sampling of frequently tasteless people. Right now we prefer the emotional approach." Meanwhile, the head witch isn't worrying about such abstractions. Mostly Liz Montgomery is enjoying herself. She's a little uneasy, however, about the sudden flurry of attention being given her in the press and is cautious about her answers to questions. She remembers what she says to reporters and was particularly upset by a story in a news magazine that didn't quote any of the bon mots of a lengthy interview but preferred to go to other sources for a portrait of Liz she considered unkind and inaccurate. But this, too, is one of the penalties of success - and Bewitched is beyond question a surprise success. In some distant future, perhaps, anthropologists will find some clue to our civilization in the remarkable popularity of a television serial about a suburban witch who can resort to magic when everyday affairs become too burdensome. This article originally appeared in Pageant magazine's April 1965 edition. It is reprinted here for educational purposes. |

Meet

the home-screen's newest, brightest star - a lanky pixie who has only

to wrinkle hr tip-tilted nose to produce miracles. And she doesn't even

need to use a broom.

Meet

the home-screen's newest, brightest star - a lanky pixie who has only

to wrinkle hr tip-tilted nose to produce miracles. And she doesn't even

need to use a broom.