|

Submitted by Scott

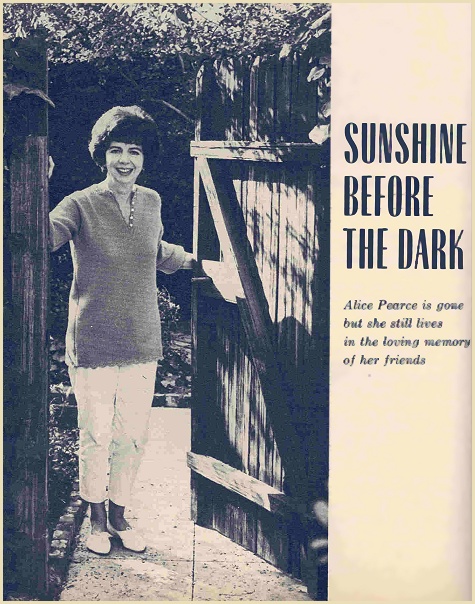

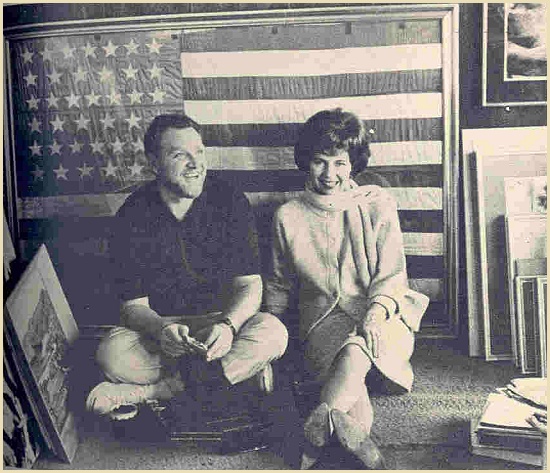

She was no star. Millions of her devoted fans did not know her real name. To them she was Gladys Kravitz, the nosy neighbor of Liz Montgomery and Dick York who tickled Bewitched viewers as she gasped at the odd goings-on in the ABC-TV comedy. Now she is gone, never to return. Alice Pearce was loved as few stars, few actresses, ever are. The tiny, chinless woman who drove her TV husband (George Tobias) clear out of his cool with her astonished and astonishing screeches—“But I saw the broom sweeping and nobody was holding it!”—was known to her vast public only through the characters she portrayed. Yet in countless homes, including Hollywood’s, the sense of loss is great. The rooms seem sadder, emptier, colder, because Alice is gone and will no longer lift the hearts of men, women and children with her gift for evoking happy, healthy laughter. It seems ironic to speak of the entertainment provided by Alice Pearce’s comic talents as “healthy.” At the height of her career, in her most successful impersonation, death stalked her every step like the shadow of an implacable hunter. Two years ago, at the age of 45, she was stricken with an illness that led to an operation. The surgeon had but to take a look, and the fearful fact was disclosed: Alice Pearce had incurable cancer. It was then, when others might have given themselves up to understandable despair that Alice began to play her finest roles. For most of her career, Alice had been applauded by movie critics as “that outrageously mad comedienne.” Now, in mortal crisis, Ms. Pearce faced her friends and public hiding her pain behind a smokescreen of clowning and funny stories. She may have been a “supporting player” in TV and movies, but she had assumed the center of the stage in real life as the heroine of a personal tragedy. She played the part so well that few knew of her ailment. It was at this strangest of moments that life also cast her in another starring role—as heroine of a tender, unforgettable love story. Nine years ago, Alice became a widow after a happy marriage with John Rox (songwriter of such hits as “It’s A Big, Wide, Wonderful World”) and long mourned her loss quietly and alone. In 1964, still reeling from the report that her malady was “terminal,” she faced a momentous decision. For some time, Alice had been dating director Paul Davis but somehow never felt ready for a second marriage. Now, she could either reject her ardent suitor, shrouding her remaining months in darkness and disappointment, or she could do the incredible—by mustering her last resources of courage and marrying Paul “for as long as God gives us to make each other happy.” In September, 1964, Alice became Paul’s wife, and not even her closest friends knew the heartbreak that lurked behind the loving eyes of the seemingly blissful pair. Thus began the saga of a love that has seldom been equaled in the annals of show business. Paul Davis, a man with a huge appetite for living and with energy to burn, now gave himself completely and without a hint of regret to the care and contentment of his doomed wife. On her side, Alice never revealed by a whimper or complaint that she might be in pain. She did all and more than most normal women do to fill their home with beauty and brightness, and to give her husband a full measure of love, understanding, and joy. A friend who visited them during the last year of Alice’s life says, “She was never more amusing. She kept everyone in stitches, and the most marvelous part of it all was to watch Paul holding his sides with glee as his wife raced on with her rollicking anecdotes. None of us suspected how ill she was.” In recalling her friendship with Alice, Elizabeth Montgomery says, “I felt closer to Alice than to anyone I’d met in a long time. She was so dear, so outgoing, and the wonderful love that Paul gave her so unstintingly did much to sustain her at the end. My husband (director Bill Asher) and I felt particularly near to Alice and Paul because they were married after we met her. It had the effect of making us feel part of their lives. “Shortly after Bewitched went on the air, a writer referred to the relationship between Bill and me as ‘cloying.’ It upset me. Then suddenly Alice poked her head through the doorway of my dressing room and said, ‘Well, if you and Bill are cloying—wonder what that writer would say if he saw Paul and me? I guess the four of us should call ourselves The Real McCloys!’” Liz also recalls that “Paul was Alice’s best audience. She was full of fun to the very end. One day a still man was shooting gag pictures of her. He had her gaping at some of Samantha’s witchery and trying to hold on to a broom that was about to fly off. After a while, the photographer said, ‘Now, Alice, how about a few straight shots of you as you really are?’ She looked at him with that funny expression nobody can duplicate and said, ‘But, sweetie, I thought that’s what we were doing.’ “Paul let out a howl of laughter. It just broke him up. You know, he gave himself to her. There had been two things Alice always yearned for—to own an art gallery and to write a book. “Well,” says Liz, “when they got married, Paul saw to it that they opened Pesha’s Gallery and Framing Shop. Then, to fulfill her second wish, Alice began a journal. During the last period of her illness, she kept making notes in it. She had the idea that keeping a record of her daily symptoms, her bodily reactions to the drugs that were administered, might be of some help later in cancer research. It was typical of her to think, almost with her final breath, of others rather than herself. “At all times, good or bad, she held steadfastly to a show of good cheer. Paul said afterward, ‘I knew she did this for me and for her friends…to spare us unnecessary anguish…”

One of the quotes from the journal proves that this indeed was foremost in Alice’s mind. She wrote: “I am a supremely happy woman in spite of my illness. I was never beautiful or glamorous, but I was blessed nevertheless with a rich career and the love of two fine men. Especially in the devotion of my dear Paul, have I found strength beyond measure. I am humbly grateful for a beautiful life….” As the cancer grew in virulence, her flesh seemed to melt away. She weighed only about seventy pounds when she died. But when an unknowing actress friend asker her for her reducing diet, Alice merely laughed heartily and, without blinking an eye, replied that it was a “secret that she couldn’t divulge.” Actually, although she often made light of her physical charms, she was never considered lacking in the attributes of feminine appeal. To quote Gene Kelly, who worked with Alice in On The Town: “To me, she was really beautiful. I never saw her without thinking, ‘What an utterly lovely woman this is.’ And I know that I was one of many who thought so. Her flashes of wit, her authentic talents, and her interest in the people and events around her, set her apart as a woman created for love and happiness.” This sentiment is echoed by another friend, Debbie Reynolds. “I was hardly alone in loving Alice,” says Debbie. “Everyone loved her. She was a rare person, one of God’s very special people. What was she like? Well, she was like a little hummingbird, very sweet, very busy, very tender. I first worked with her in 1952 at the Dallas State Fair Theater in Best Foot Forward. Then she went back to New York, and we never met again until four years ago. We were making My Six Loves at the time, and she was a living doll to work with.”

Remembrance of laughter “It was funny, she couldn’t drive but her part was that of a driver of a school bus, Well, in her first scene—she’d never told the director she couldn’t drive—she was supposed to take the bus a certain distance and stop short, but Alice kept going until she ran into a wall. Out she came with that laugh of hers: ‘There are two pedals down there and I’ve forgotten which one is the brake.’ “On the next take,” Debbie smiles reminiscently, “she was to push a button that opened the bus door. She fiddled around and finally quipped, ‘I must have lost my buttons.’ Finally, they put a man in the bus and had him lie on the floor to push the brake and button, but then she shifted gears without putting in her clutch! “Anyway, but the time they finished, I was whooping so hard all my makeup was spoiled and had to be redone. Her timing was perfect. When you were in a scene with her, you just resigned yourself to having it stolen from you.” Debbie was one of those who first noticed Alice’s loss of weight. They were appearing in a skit together at the Thalians’ Ball. “I said that she was looking like a young girl, all trimmed down,” recalls Debbie. “She winked at me and said, ‘Yes, I’m out to become the newest sex symbol in Hollywood.’ That was last September, and her friends still didn’t realize she was ill.” Jerry Davis, producer of Bewitched, testifies to the fact that “Alice worked to the day she could no longer stand on her feet. We all were aware by then that she was sick but never discussed it with her because we realized that was the way she wanted it. She appeared before the cameras for the last time on January 21. “The episode in which she was last seen was shown on television a week after she was gone. All of us watched it. All of us wept.” Another who admired and mourned Alice Pearce was Agnes Moorehead, who plays the mother-witch, Endora, on the show. In a voice trembling with grief, she recalled, “Alice and I had many things in common. For one thing, she was an eccentric, and so am I. I’ve always felt that it was wrong to hold back on eulogies until after people are dead. Why not tell them how you admire, respect, or love them while they are still able to appreciate it? In the case of Alice, I do believe she knew how we felt about her, and this goes for the crew as well as the cast. She was always kind and considerate of everyone. “She was lucky in one respect. She had Paul. So few of us can say as much. It is not easy to find a love that true, faithful, and wholly committed. It was thrilling just to see them together, he so attentive, she so glowingly proud and happy that this much-admired man was hers.” Dick York points out: “It was impossible, no matter how down the company was feeling, not to be cheerful around Alice. She never brought any problems to the set. Her illness would have given her every right to be irritable, but she never was.” Richard Deacon of The Dick Van Dyke Show was an especially close friend of Alice’s in the last four years. As he tells it, “we met through a mutual friend a long time ago in New York City. She was the type of human being that nice people insisted on passing around as a favor to other nice people. They introduced her as if they were conferring an honor, and it was. She had a genuine genius for friendship.” He was one of the few “honored to be left a goodbye note from Alice.” It moved him deeply. The note was serene and brief. It said: “Thank you for being a wonderful friend. Please look after my Pesha (Paul in Hungarian) as he will need friends now, and please give my love to the two great ladies, Jane Dulo and Cynthia Lindsay.” Richard (“Deke as he is known to friends) likes to reminisce about Alice. “One night I arrived at her home and said ‘I need a needle and thread. The seat of my pants split.’ I was pretty embarrassed—not only because of my pants splitting but because I’d gained weight and none of my clothes fit! And, as it happened, that was the night we were to fly to Las Vegas for an opening. “Alice, I might add, was dressed to kill in a blushing-pink dress with matching coat. As we were leaving for the airport, Alice saw that I was still feeling embarrassed. So she said, ‘Look, Deke, I want to show you something.’ Then she took off her coat and showed me that her lovely dress was entwined from neck to waist with white shoelaces. “’I split my dress because I’ve gained too much weight too,’ she told me. ‘And this is how I fixed it for tonight! So let’s make a bargain. Neither of us will remove our coats and we’ll eat like sparrows tonight.’”

Remembrance of a lady Although she refused to discuss her illness, Richard knew the worst, and tried to find reasons for sending her flowers as often as he could. Alice, he smiles ruefully, always played the game of not understanding what he was up to. The last ones he sent her were for Valentine’s Day. “I addressed the card ‘To My Valentines,’” he explains, “which would include Paul. He, too, played the game and never let on for a moment that her illness was terminal. “Two days later, I received a thank-you note from her. It was dated Feb. 16—and on March 3, she was gone. Think of that greatness. How did she ever find the strength and resolution to attend to such a small matter when she knew death was so near? But then, of such quality was Alice made. She was a lady through and through.” The two “great ladies” mentioned by Alice in her posthumous note to Deacon are still shattered by her death. Asked to recall “something typical” of her friend, actress Jane Dulo replied, “Since Alice didn’t drive, I told her she should call on me any time she needed to go shopping or for an interview. It was when she first came out here. But, as I expected, she didn’t call. She hated to impose on people. She simply took taxis. “It was this same feeling of consideration that prevented her from confiding her trouble to anyone. She preferred to make her friends feel that everything was coming up rosy.” Jane worked with Alice in the Broadway version of On The Town, in which Alice had a featured role and Jane understudied the star, Nancy Walker. “The first night I had to step in for Nancy, Alice was as excited as I was. She couldn’t have been more helpful. “She was a wonderful listener, interested and sympathetic. But basically, I’d say she was a loner, in spite of the love she inspired in all sorts of people. I knew her a year before I went to visit her in her apartment. That’s when I discovered her talent as a painter. She’d never mentioned it before. “Later I learned other things about her—that she was crazy about antique and thrift shops; that she never felt quite dressed without a hat, usually one with a kooky little touch. She was also one of those people who manage to be proper without being stuffy. A dear, absolutely feminine, womanly woman.” Cynthia Lindsay, author of The Natives Are Restless, Mother Climbed Trees and many other books and teleplays, found it difficult to speak of her lost friend. “It’s so strange,” she mused. “I didn’t know Alice for a long time… and yet I feel as though I knew her so well.” It is perhaps one of the finest tributes to Alice Pearce. Many others in show business have offered their bouquets to this remarkable woman. Imogene Coca, Nancy Walker, Carol Channing, and Ethel Merman are among those who expressed their high regard. But clearly, the most touching and emotion-laden offering to Alice was given by the man she adored in life, her husband, Paul Davis. At her request, there were no funeral services. A small, bereaved group attended the cremation of her body. Still following Alice’s wishes, Paul rented a plane and, with shaking hands, scattered her ashes over the billowing Pacific, in the direction of Hawaii, where they had spent a belated honeymoon. She had always loved the sea, finding it both mysterious and calming. The man who had bathed and fed her when she was too weak to function on her own; who had nursed her, given her the pain-killing injections, lifted her on and off her bed in order to smooth her sheets or change them—and who wept in the privacy of his room as the hour of their final parting approached—Paul Davis managed to express his profound grief. “A week before Alice died,” he said in a strangled voice, “she asked me whether I believed in miracles. Knowing there was no hope for a case of terminal cancer, I still felt I must make a pretense for her sake. I smiled and said, ‘Of course I do, darling—and so must you.’ She smiled back at me. ‘I’m glad. Because you know, dear, we’ve already had our miracle.’ “She was never bitter. One day she said to me, ‘God closes one door only to open another.’ I somehow know that this is true. Alice never went into a coma. She said goodbye to me just before she died. “For as long as I live, as God is my witness, I will

never forget the wonder of what happened to me these past couple of

years. I’ll never forget the miracle that was Alice Pearce and

the love we shared.” |